K E N T M A T S U O K A

Untapped Resources of the Armed Forces

When Top Gun was released 30 years ago, the Pentagon’s attitude towards Hollywood was thought of more as an annoyance but has since been recognized as a watershed moment in military involvement with Hollywood as enlistment numbers spiked in aviation fields and the Military brass began to recognize the soft power potential of partnering with Hollywood.

The U.S. Military had been experiencing draw downs following Vietnam and the thawing of the Cold War made it harder and harder for Congress to justify their burgeoning budgets to their constituents as films critical of the military shined a light on the absurdity of war. Along came Top Gun, and having the fastest, most technologically advanced warfighters became a justifiable expense again.

Properties in the Action and Adventure genres still consistently rank as some of the highest grossing movies worldwide, with films and television series distinctly based on the military such as The Long Road Home and Lone Survivor featuring extensive military cooperation, but can also be seen in films as varied as Transformers, Bridge of Spies, and even Pitch Perfect.

The one component each of the above films have in common is that they all cultivated a favorable relationship with the military to provide access to a wealth of history, information, and military hardware unavailable anywhere else.

How does the U.S. Military reach out to Hollywood and offer what has been coined an act of mutual exploitation to the studios that take them up on the offer?

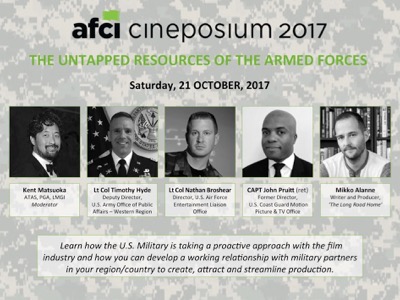

To help me answer the question, the AFCI asked me to speak with some friends last week on a panel at Cineposium about how the U.S. Military takes a proactive approach with the film industry, and how film commissioners can develop a working relationship with the military partners in their region to create, attract, and streamline production.

•

I turned first to writer and producer, Mikko Alanne, and Lt Col Timothy Hyde, Deputy Director of the U.S. Army Office of the Chief of Public Affairs, Western Region (OCPA-West), and discuss their experience filming The Long Road Home at Fort Hood in Texas.

The series is based on units of the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division during an ambush in Sadr City in 2004 that’s now known as Black Sunday. Based on a true story, it was only natural that Mikko approached the Army for cooperation, and was glad to find them interested and willing to help.

Fort Hood is the home of the 1st Calvary, so Mikko initially planned to film the backstory there, using base housing and Garrison HQ to play themselves. As development progressed, they found that the usual suspects of Jordan and Abu Dhabi weren’t good matches for Sadr City, and couldn’t provide the Bradley Fighting Vehicles 1st Cav operates. NatGeo risk management obviously nixed any ideas of actually filming in Iraq so Mikko circled back to the Army to first investigate training facilities such as Fort Irwin’s National Training Center before deciding to build their own replica of Sadr City at Fort Hood.

Mikko also took advantage of the highly trained workforce available to him on base, and hired many soldiers on liberty to play themselves as background, supplementing the area's limited talent base with hundreds of willing volunteers wearing the uniforms they wear every day and operating equipment they already knew how to use without additional instruction from technical advisors.

When it comes to outreach by the military, the U.S. Air Force has consistently been proven one of the best of any government organization, and Lt Col Broshear, Director of the U.S. Air Force Entertainment Liaison Office continues the examples set by his predecessors. The Air Force has been the only military office present at the AFCI Location Trade Show, and understands the importance incentives and infrastructure, taking those needs in mind when recommending various bases for filming.

They’re active in conducting military FAM tours to introduce writers, producers, and production executives to military assets and job specialties that can be incorporated into potential projects, and provide plenty of opportunities for those influencers to speak one-on-one with airmen and officers who have opened more that one participant’s eyes to the diversity and range that the Air Force can offer.

Such outreach has served the Air Force well, with the inclusion of specific Air Force content as varied as Tyrese Gibson’s Air Force Combat Controller character in the Transformer series, reference to Chester Sullenberger’s experience as a Air Force veteran contributing to his cool calculations in Sully, and providing historical research materials and access to the U2 aircraft in Bridge of Spies.

Additionally, Lt Col Broshear mentioned that the USAF’s long relationship with the Royal Air Force helped Transformers: Last Knight gain the permission needed to film with RAF and USAF assets in the United Kingdom that might otherwise have been denied.

Producers have long looked to international partners to gain access to assets otherwise unavailable in the United States. Francis Ford Coppola famously filmed Apocalypse Now in the Philippines partially because Marcos agreed to lend Coppola the Bell Huey helicopters needed for the pivotal scene with Robert Duvall after the DoD denied assistance due to the film’s anti-war message.

CAPT (ret) John Pruitt, USCG, is the former director of the U.S. Coast Guard Motion Picture and Television Office (MOPIC) and was responsible for consulting and advising the Canadian Coast Guard regarding filming during his tenure at MOPIC, as well as having spent time training various other Coast Guard and Naval units around the world as a ship commander and was able to offer his experience working with different military services.

CAPT Pruitt stressed the advantages for film commissions of smaller countries to reach out to military partners, especially when they’re such a visible presence in the community. He pointed to his experience in the Caribbean where the Royal Bahamas Defence Force and the Jamaican Defence Force routinely work in concert with the Police and Constabulary due to the transient nature of the region, and are often among first locals a tourist would see upon arrival to their country. Larger countries such as Canada and the Philippines could potentially provide American assets to draw American productions that might otherwise be unavailable from the U.S. itself, as seen in the example of Apocalypse Now.

Military forces also often own large tracts of land, much of it left undeveloped as seen with the example of The Long Road Home. The film Dunkirk also surprisingly filmed on U.S. soil, despite being a historical story that the U.S. military had no involvement with, nor would feature any U.S. military assets or personnel.

On Dunkirk, Location Manager Doug Dresser approached the U.S. Coast Guard to film at the Point Vicente Lighthouse in Los Angeles, where they came to film interior stage scenes and edit. Nolan wanted to film the close-up scenes of Tom Hardy piloting the Spitfire on a cliff with 180˚ views of the ocean so Dresser scoured the California coast for a large south facing flat pad without breaking waves or obstructions to match the aerial scenes filmed over the English Channel. The only viable option they came up with was at Point Vicente.

The U.S. Military operates on strict guidelines to prevent corruption, either through the appearance of subsidizing a private corporation with taxpayer financed assets, or by taking away business from a private companies that might provide a similar service. For this reason, the U.S. Military can only cooperate by providing something that isn’t publically available in exchange for positive media exposure they wouldn’t otherwise get.

Since the Coast Guard could not expect to get direct exposure through inclusion of Coast Guard assets or personnel in the film, they had to first insure that Dunkirk had exhausted all commercially available options, then work out a way to get the media exposure needed to justify the use through inclusion of DVD interviews and special features about the Coast Guard’s mission and involvement.

The State of Hawaii went a different direction with the U.S. Navy last year. Honolulu has faced a shortage of available stage space in recent years and was looking at the former Naval Air Station Barbers Point property which was closed through the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) downsizing in the 1990’s. Much of the base had already been transferred to State control for use as Kalaeloa Airport and they wished to proactively include an underutilized maintenance building for use as a stage. Luckily, the State of Hawaii was able to finalize an arrangement with Navy Region Hawaii to lease the property themselves in time to sublease it Marvel for Inhumans last year.

As we know that crew and infrastructure are just as important as the creative requirements of appropriate locations, for the film commission looking for a slight edge over their competition, if you’re not already taking advantage of the Military's unique assets, experience, and real estate in your area to add to your own efforts, you could be leaving a significant chunk of the pie on the table.

I've written several articles about the lessons we can learn from the Military here and on LinkedIn. Please check out similar articles like this one below.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The Hollywood and the Military

Veteran portrayals in the Media

Sunday, October 29, 2017